Always a pleasure.

The Works of Rybread Celsius: A Critical (Re)Assessment

2016-03-25 · by Anya Johanna DeNiro

tagged Blog / Opinion / Reviews

“I think that one day Rybread is going to successfully get what’s

churning around in his mind written & compiled and present us with an

absolutely stellar adventure game. And after giving us three weeks to

play it, I predict he’ll then blow up the earth.”–Robb Sherwin on L.U.D.I.T.E.

When I first became involved in the interactive fiction community online, back in 2001, my head was blown open by the possibilities afforded by parser-based games. I dutifully tracked down a copy of Lost Treasures of Infocom to find my footing with the “canon” that most others were building from. But there was someone else who seemed to be working on the fringes of the community–who some people considered an Ed Wood-type figure making monumentally bad game after game. Many considered him the worst writer of interactive fiction on the contemporary scene. Still others, fewer in number, considered him one of the experimental geniuses of interactive fiction. His name is Ryan Stevens, but he wrote under the name Rybread Celsius.

I have to say that I found myself in the latter camp right away. Today his work is largely forgotten (which, to be fair, has happened even to many works that were immensely popular in the late 90s and early 00’s). A lot of times he appeared to be banging his head against the constraints of Inform 6, trying to bend and twist the form of the parser game into something that fit his idiosyncratic vision.

Often broken in a very real sense, rife with typos (deliberate or not?), bad default messages, and constant point of view shifts—and largely unplayable without a walkthrough—his games entered in the Interactive Fiction Competition always scraped near the bottom places.

They are eminently difficult to describe.

There’s Symetry (1997, 32nd out of 34 places), the story of a sinister mirror and a letter opener. “Tonight will be the premiere of you slumbering under its constant eye.” There’s Lurk. Unite. Die. Invent. Think. Expire. (1999, 35th out of 37 places), with rooms such as the “chaos hymn point” and a koan-like winning command that…okay, would probably be difficult to come up with on one’s own. There’s “Rippled Flesh” (1996, 24th out of 26 places), an earlier effort that plays it fairly straight but nevertheless yields several surprises.

But his crowning achievement—at least for me—is Acid Whiplash (1998, 23rd out of 27 places), its title the closest thing to an ars poetica in his body of work. In the preface there’s this:

“Rybread Celsius casts two shadows. One speaks. The other sickens. (They also have a great dance routine.)”

And there’s this:

Note: At any time, type WALKTHRU for a complete solution to the puzzle at hand.

>walkthru

Walk though what? >

It includes perhaps my favorite room description ever: “A tiny little room in the shape of a burning credit card.”

And room descriptions like this:

Hermit’s R00m Tilly The Tacky leaves here. He is a hermit. He reads “Walden” twice a year. He thinks he is cool, but he’s not, he’s snot. Currenty he is not here. The room is pretty bare. Not tacky at all.There is a beaver and a cheese cloth, prolly his bedding.

You can see a Tooth Beaver here.

At one point you also enter the Pope’s hat, and elsewhere into a truck dashboard while co-author Cody Sandifier and Rybread have a long conversation:

[Sandifier]: In Symetry, the response to GET IN BED is “But you’re already in the Your Bed.” I love your mixing of articles and possessive adjectives — especially since the player is actually *outside* the bed. It’s this sort of interior/exterior dualism that strikes me with a pleasant chill.

[RC: The bed struck you? I don’t remember coding that. Hmm, but it’s a good idea. I think the best things are that is all shielded in a thin bit o’ seriousness, just waiting to explode with the insanity of Brazil.]

The madcap humor wouldn’t work if it wasn’t so self-deprecating (and of course, your mileage may vary—it is laid on quite thick), and aware of his own status as cult figure (of sorts) within the IF community. Lots of the interviews delve into the strangeness of his games, with interviewer Sandifier providing an almost fawning, lit-crit sheen onto the proceedings. In a way, the interview becomes a retrospective of “favorite scenes from previous Rybread games,” and his work certainly invites this, because they are so hard to describe in terms of narrative. If there’s a skein of images, it becomes (somewhat) easier to pluck one or two out, since the context between the images is rather fragile to begin with.

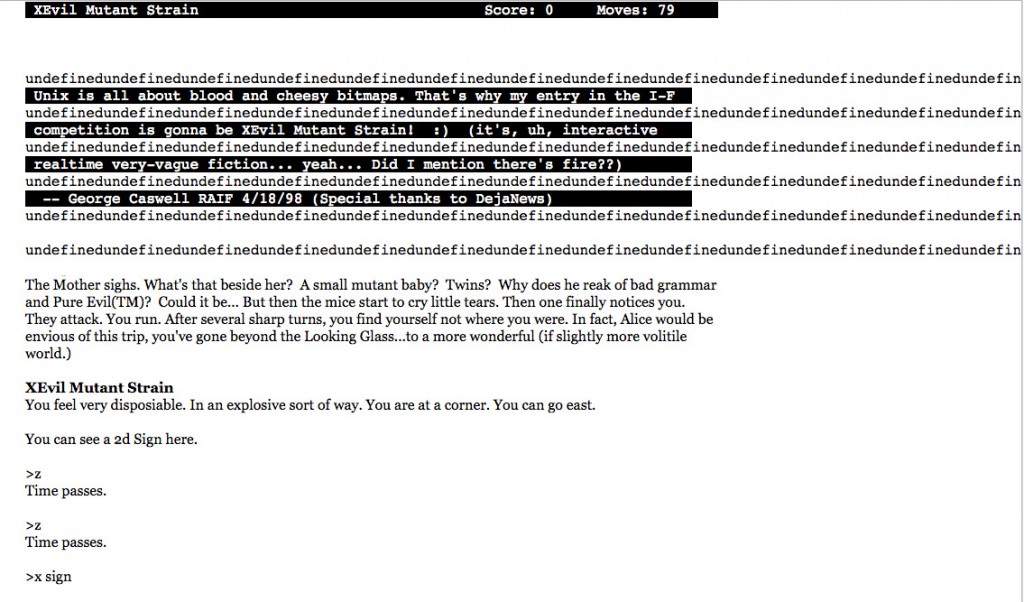

Even when the images did their best to break:

But what really interests me about these games now is looking at them through the lens of the recent “Twine Revolution”—the wide swath of games made in Twine and other mostly choice based platforms that elide concrete meanings, use langauge like buzzsaws, and take huge cognitive and temporal leaps from one passage to another. The key here is passages, of course. The core unit of organization in a work of Twine (a passage of text) is usually very different than in Inform (a room). But Rybread’s work is the closest parallel to an experimental hypertext work in parser form—and he was doing it 16 years ago.

But Rybread was enamored of the parser form. He clearly loved the history of interactive fiction, and loved riffing off Infocom (“Caecilius est pater. Metella est mater. The last lousy point can be won by… but no. That would be telling. Well, what the hell, I’ll tell. The last lousy point is rot13.”) he writes in the >AMUSING section of Acid Whiplash.

And the games are rife with puzzles. They are, most often, broken puzzles, but the design form that Rybread was working with absolutely took its cues from the Infocom classics and the “first wave” of the hobbyist IF community in the 90s.

Authorial intent is often tricky to discern—but what did Rybread mean to do with his games, after all? Maybe then it would be possible to intersect those aims with those of more recent Twines. I was pleased to find the closest thing to a more-or-less coherent “artist’s statement” by Rybread in the IF Theory Handbook:

Myself, I have ideas. And try to express them. But it’s like some sitcom father trying to get all the clothes into suitcase. They overflow, wrinkle and escape. What’s left is some sad ready-made. The line between a bad game and a Dada game need not exist, they share the same Venn diagram. But the attributes expand. There is the sense of the uncanny and stupid, without stepping into the realm of surreal (a more fleshed out plane), but ghosting its border. … Grammar mistakes and coding ineffiencies paint miniscule portraits of the author’s states.

This idea of “ghosting borders” is certainly one that some experimental Twine games play with—“glitching” a game to provide a heightened sense of fracture or confusion. For example, in b minus seven’s Inward Narrow Crooked Lanes, the if/then statements are embedded within the player’s field of vision. The scaffolding highlights the sense of playing a game (in fact, during the 2014 IF Comp when this game was released, it became a discussion point as to whether this was intentional or not; whether it was a “bug” or not):

Leaving “broken” pieces in plain sight is of course a technique that has a long life from early Joycean modernism to postmodern cut-up. So perhaps the closest similarities don’t have to do with content, but rather process: bending an interactive fiction platform to get at something. The words and connections appearing to rush out of control because of an inner state that needs to be expressed. Of course, no game is “immune” from this—even the driest puzzle fest is an attempt to communicate an interior desire by the author. But in both Rybread’s games and later “personal” or more experimental Twine games, the author is trying to disassociate the player in order to convey a mental state or something “uncanny”, and giving the player an opportunity to navigate this disassociation. In Porpentine’s Cyberqueen (2012), language melts (“thousandfold armlungs breathing datapotence) as you the player-character become more and more trapped, more and more caught in the visceral embrace of the Cyberqueen. For Porpentine’s signal works, the word disassociations are at the service of a profound, almost unbearable sense of alienation, while for Rybread it’s more for anarchic play and, in later games, a winking awareness of his own status in the interactive fiction community. Maybe this is the difference between tragedy and comedy in gaming. (Though games like Crystal Warrior Ke$ha and High End Customizable Sauna Experience certainly display Porpentine’s wicked—and invitingly collaborative–sense of humor.)

And for me, since coming into the IF community in 2001 and joining Team Rybread, I have definitely changed as a player and creator, and I think I’ve grown as well. In 2001 I was 28 years old, still only a few years removed from poetry grad school in a homogenous college town and, well, still fairly precocious. My first forays into interactive fiction were in the parser form (ALAN, actually). Now in 2016, I’m a parent to four-year-old twins, I’ve recently come out as transgender and what excites me about interactive fiction has certainly evolved. Recent games—both choice and parser-based have a depth and breadth that is unparalleled in history of the field. And in particular, interactive fiction works from queer authors have certainly sustained me when I still wasn’t ready to articulate who I was in public.

So I have complicated feelings about my own devotion to Rybread Celsius’ games. I still love them, particularly Acid Whiplash, but I’m also acutely aware of their limitations—not in terms of experimental content, but in terms of heart, and putting risky content (which might confuse your audience) at the intersection of the emotional and the political.

But I have to remind myself that influence doesn’t happen in a straight, neat line most of the time. I have to give myself permission to have complicated feelings about things that I liked when I was in my 20s. And I encourage you to try out some of Rybread’s games yourself—perhaps you’ll take your own inspiration from them, in a way that couldn’t even be conceived 15 years ago. That’s perhaps the beauty of interactive fiction as a living, breathing tradition—one that the “Twine Revolution” is certainly a part of.

Anya Johanna DeNiro is a two-time XYZZY Award winner and the author of IF works such as Solarium, Deadline Enchanter, and Feu de Joie. She can be reached at www.goblinmercantileexchange.com and @adeniro on Twitter.

The Works of Rybread Celsius: A Critical (Re)Assessment

by Anya Johanna DeNiro- Buy the author an iced coffee

- Share this story on Twitter

- Follow the author on Twitter